“Well, here comes the circus, Daddy.”

Big Minch, aged eight, had spotted a white HiLux grinding up the track while Wes had his head under the bonnet of the Bedford trying to divine where the boost from the alleged brake booster had boosted off to.

“Circus?”

“Yep, Daddy.”

“I’m dubious, son. Circus folk head for population centres, not the back of nowhere up a dead-end valley such as ours.”

“It’s him.”

“Wait! It’s him? It’s who?”

“Tyson, Daddy. Mr Tyson Buntley.”

“Run! Hide! No, it’s too late. Why did you say the circus was coming?”

“Well, every time he comes here it’s just like the circus, Daddy.”

“I can’t argue there. You’re right, Minchy. More spills than thrills. Run and tell your Mum to warm up the First Aid Kit.”

Tyson Buntley was not a bad man. He was not a mad man. He wasn’t unrelentingly stupid.

He was what Alice Piddens referred to a “a functioning dill”.

Tyson’s first, and last, paid job had been dairy hand on some place near Orange or Tumut or some other chilblain centre. In those frosty parts it was standard practice for a worker to start the day by plunging his/her gumbooted foot into a bucket of scalding water to thaw the tootsies a little before the teat work commenced. And Tyson followed suit. Until the day he jammed his foot in the bucket, the gumboot split, the scalding water rushed in and it commenced poaching his toes.

That was bad enough, but …

“Ayayay! Aaaargh!”

The boot got stuck in the bucket, so Tyson tried to kick it off. It worked. The bucket, boot and water came off as a unit and sailed through the air.

And smacked the boss in the face.

“Oops! He’s copped the whole rizamarole!”

It knocked out several teeth. Even after the broken jaw had been set, it sat so far sideways that the boss’s head looked like the freeze-frame shot of a Kostya Tszyu knockout punch.

The boss could not chew. He could not whistle. He would not forgive.

Tyson’s dad saw the writing on the dairy wall. Long-term employment was not in his golden son’s stars. He would have to buy Tyson a job. And so, it came to pass that Buntley Senior purchased the property next to the Piddens spread, renamed it Cedric Springs and installed Tyson as Manager.

And what a canny investment that turned out not to be.

Although nominally on a tight leash, the ‘Manager’ effortlessly found golden opportunities for stuff-ups and by the time he had attended to his hobbies there wasn’t too much of the day left for farm work.

It didn’t take him long to get on the wrong side of easygoing Johnny Ham.

“You got any mice, Johnny? Or rats?”

“More than enough, mate. Thanks for asking.”

“Wanna sell some? Regular?”

“Sell ‘em? Regular? I want to exterminate the bastards. Once, and for bloody all! What do you want with mice and rats?

“I need a regular supply to feed my snake.”

“Your snake?”

“My python.”

“By the livin’ Harry, I’d go for a long time before I fed a bloody snake. Set him free in the bush to catch his own.”

“But he’s institutionalised.”

“What?”

“Ceddy lives in a fish tank. He’d never survive in the wild.”

“Ceddy?”

“He’s good company.”

“You want company? Let your dog sleep on the veranda.”

But the straw that got the camel’s back up was Tyson skinning his horse.

The horse died, possibly from boredom. Tyson skinned her and made the pelt into a rug. Put it in front of the fireplace as a conversation piece for him, Ceddy and the occasional, astonished visitor.

When Johnny Ham found out, he vented at Wes.

“Skinned his horse! Skinned his poor old bloody horse, mate. He’s the one wants skinning!”

Wes, too, was alarmed.

“It’s pretty alarming. I’m certainly alarmed, that’s for sure.”

“Alarming? Alarming? Mate, I went to the war. I saw men do things … but I never knew anyone to skin his own horse. You don’t skin your old mate, mate. You just don’t!”

Tyson eventually fell in love and got religion. As with all creation myths, it was hard to work out whether it was the chicken or the egg that got cooked first.

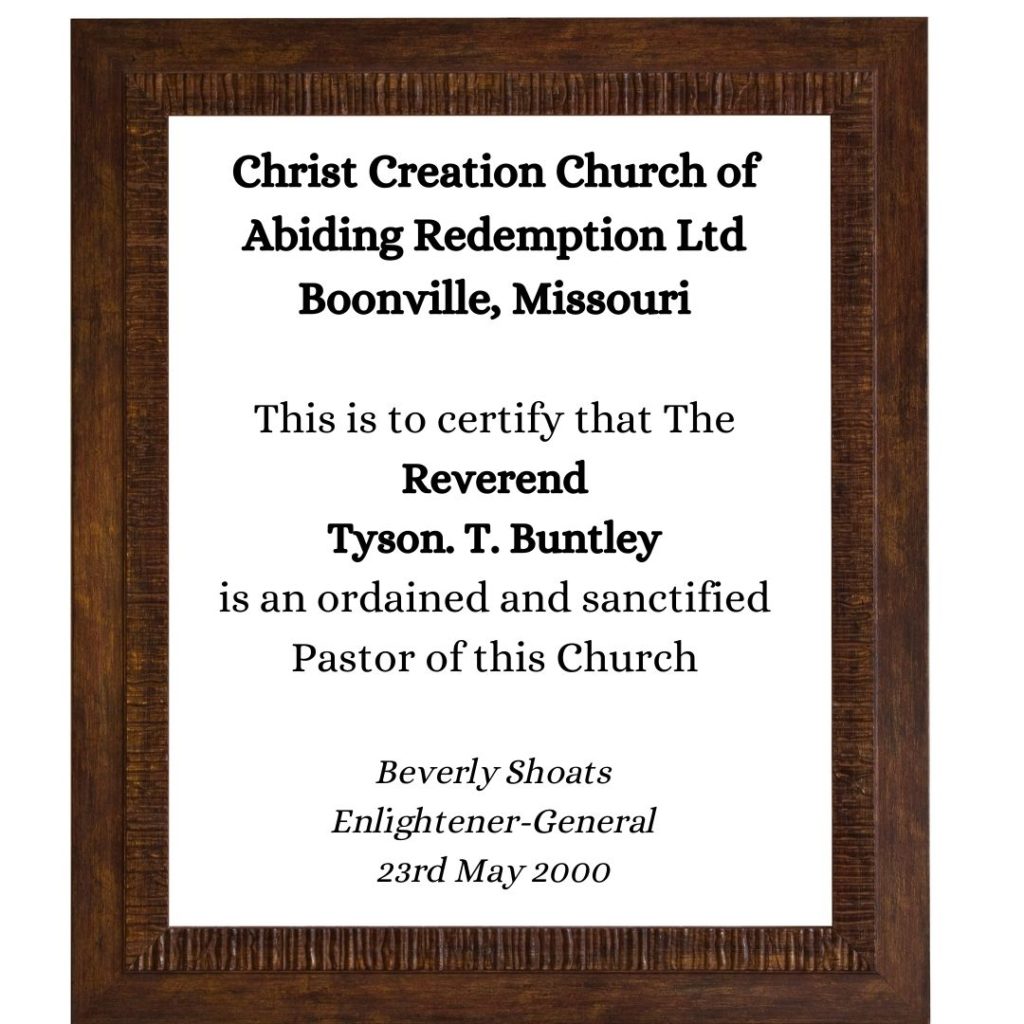

Wes’s first inkling came when he spotted an imposing framed certificate on the wall of the ‘Horse Rug Room’.

Tyson followed Wes’s astonished gaze.

“Not bad, eh? You do the course by mail. Takes a week. The whole rizamarole costs five hundred bucks, which is pretty good value for a real degree. Then your diploma arrives. Frame extra. Plus postage. I can sign you up, if you want to be saved.”

“No, no. I’m covered, thanks. Alice is my Judge and Protector.”

“Well, bless you, anyway.” (elaborate enigmatic hand gesture like something out of the Three Stooges)

Then Rebecca entered the picture. She was an “Auxiliary Pastor”. Apparently over in Boonville they took a dim view of women sticking their heads up too high, but suitable women, upon payment of an “administrative donation”, could be duly ordained to support the ongoing mission by way of household choring and “supportive submission”.

Wes got the impression that their wedding had been carried out by mail order.

Either that, or they’d officiated at their own wedding. The Wedding Certificate went along similar lines to their Certificates of Ordination. The main thing, according to Rebecca, was that they hadn’t “lain in sin” before they “domiciled”.

“Well that’s sweet, I guess,” was Wes’s best response.

Rebecca was nice enough, and good for Tyson, pretty much. His grooming and personal hygiene improved (or, rather, commenced); he got more farm work done; the horse pelt retired to the barn and Cedric disappeared, never to be spoken of again. Clearly, Rebecca wasn’t jinxing their “Holy Union” with a “serpent in the bosom of the family hearth”.

And Tyson had certainly cut back on his customary cussin’.

Wes rocked up to their yards one day to give them a hand with branding. It looked like a gala event. Rebecca had set up a card table under a beach umbrella and laid out all the vaccines, stock lists and tagging gear. The branding iron was heating, the cattle were drafted and ready and the happy couple stood holding hands. Spirits were high.

The morning went pretty well. There were the usual uncooperative/stroppy/ escaping beasts, but everything was handled pretty efficiently. Of course, there were slips, booboos and stuff ups.

“Oh, goodness me. Sorry, Darling. I opened the gate too soon.”

“No, that’s fine, Sweetheart. There’s not too much blood. I’ll put a Band-Aid on it later.”

“Love you.”

“Oops. I put that tag in back to front. Sorry, Darling.”

“No, no. It’s fine. That calf will be easier to remember, Darling.”

“Bless you, Darling.”