Michael Burlace

Flash floods happen quickly and usually go away after a short time.

But in February, it was different.

When we get torrential rain for hours and hours, we can get flash floods.

They are often localised – happening in a small area.

But in February and March, the rain was right across our catchment, with rain coming down the Richmond and its tributaries from beyond Bangalow, beyond Toonumbar Dam and all across the massive area.

Flash floods like this usually happen when there is up to six hours of intense rain.

But we had days and days of it.

And, after two years of La Nina conditions, our catchments were wet – soils were saturated (they had 70–90% of the water they could hold) and our dams and river levels were high.

The saturated land could not absorb much of the rain.

This meant most of the rain that fell had to run off and ideally run away from where it fell.

But there wasn’t enough room in our creeks and rivers to get the water downstream and into the sea. They were already nearly full.

The flash flooding overwhelmed our local drainage systems – valleys and creeks – and this caused many creeks and then rivers to burst their banks.

The deluge

On February 24, a cell of high pressure air sitting over New Zealand effectively blocked a low pressure air cell that was east of Queensland. This prevented the low moving away from our area.

This low pressure area slowly deepened (the pressure dropped and the cell enlarged) and moved closer to the North Coast.

This low drew a large volume of warm moist air from the Coral Sea towards us.

More low pressure air zones joined up to create a massive zone of low pressure and this funnelled moist air (holding a lot of potential rain) into our area.

As more and more moist air arrived, the fine droplets that the air could support joined with other fine droplets in the air.

This joining of droplets went on until they were too large and heavy for the air to support them and they started to fall – as rain, rain and more intense rain.

We felt the worst of that as the rain hit the land and filled our rivers and surrounds with a spectacular amount of water that could move only slowly to the sea via Ballina.

Record flooding devastates Lismore and downstream towns

Lismore is at the junction of Leycester Creek and the Wilsons River.

It endured devastating flooding on February 28.

The river peaked at 14.4m from 1pm to 3pm, overtopping the riverbank levee (10.6m) and flooding much of the commercial and residential heart of the city.

This was more than 2m higher than the record flood of 12.27m in February 1954.

The water continued downstream and joined the Richmond River and flooded the lower part of the catchment.

The Richmond peaked at Coraki at 7.65m on March 1, higher than the March 1974 peak of 7.01m.

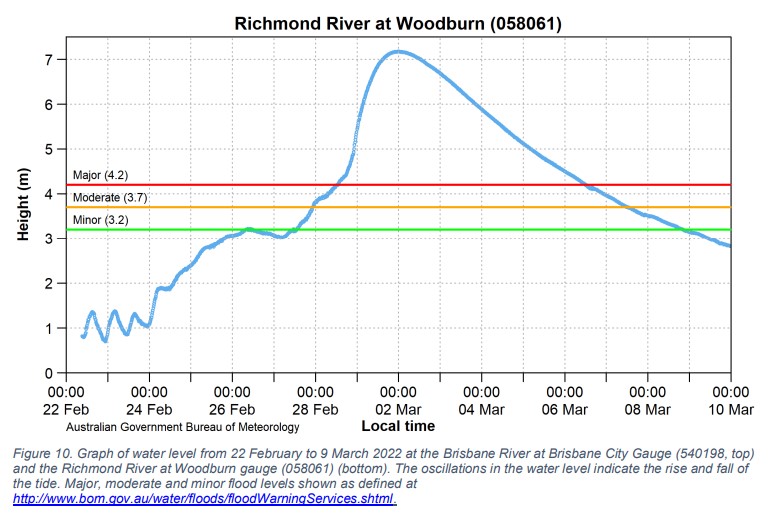

It peaked at Woodburn at 7.17m, well above the major flood level of 4.2m (Figure 10, bottom) and about 1.7m higher than the February 1954 peak (5.42m).

And Kyogle and Casino were flooded.

Draining it away

Water runs downhill and into the gullies and valleys and then into creeks and into rivers.

The rivers run downhill to the sea.

If the river can’t drain the water fast enough, it builds up and up until it starts to overtop the banks.

This is a river flood beginning.

Often, this overtopping will damage the bank and that will create a deeper gap and allow more water out.

And so it goes.

Why are river heights higher in Lismore than Broadwater and other areas nearer the sea?

Simply because the land is higher.

Water runs downhill from the ranges to the ocean and as it loses altitude, it is less high in relation to sea level.

Those river heights are a measure of how much higher than sea level the water is.

Flooding where the river hadn’t yet overflowed

The amount of rain falling was enough to create flooding on its own.

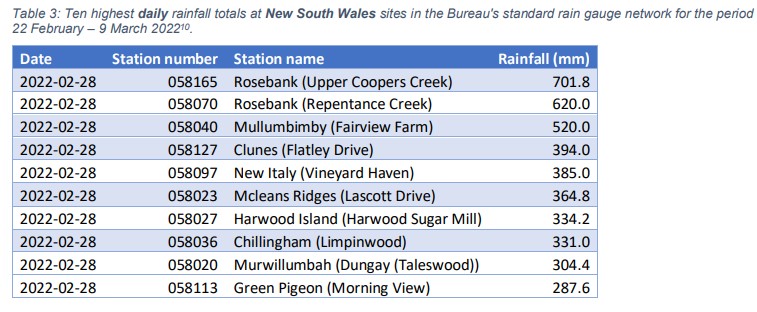

Across southeastern Queensland and northeast NSW, rainfall in the last week of February was between 2.5 times and more than 5 times the monthly average.

More than 50 sites recorded more than 1 metre – 1000mm in the week to March 1.

That’s about 4000 points or 40 inches in the old measure.

There was enough water landing on low-lying areas to flood them – even without any spillage from rivers and creeks.

If you look at the banks of our rivers you will see that many of them are a bit higher than the surrounding land.

This means the water that accumulated from the heavy falls on flat land – think canelands near Broadwater, Coraki and Woodburn – was unable to drain to the river because it couldn’t get over that bank.

Instead, it had to drain slowly across the land and into creeks that eventually found their way into the river at a point where the bank was lower or where the creek joined with the river further downstream.

That is a much slower way to drain and it left water sitting on that land for days.

The rain that fell on flat land didn’t get much of a chance to drain before it was joined over several days by the water coming down the river and overflowing onto the flat land.

The water that poured over the banks brought the flood height up even further.

The Richmond River catchment

A drop of water landing near the highest level of the Richmond River will descend hundreds of metres as it travels more than 200km to enter the sea at Ballina.

On the way it will be joined by water from multiple tributaries including the Wilsons River and Leycester Creek that contribute so much to the flooding of Lismore.

On its journey to the sea, the Richmond and its tributaries (creeks and smaller rivers) pass through Kyogle, Casino, Coraki, Woodburn, Broadwater, Evans Head and many smaller places.

The Richmond catchment is 6862 square kilometres and it has a floodplain of more than 1000sq km.

Why did the river cross the road?

Summerland Way and many local roads are next to or cross many reaches (stretches) of the Richmond River. When it floods, they may also be flooded.

Close to Ballina, the Pacific Highway crosses the river and in flood that can be reversed with the river crossing the highway.

After the flood

Then the water drained away and the cleanup was having big impacts.

People were starting to see signs that normality might one day return.

Then another flood hit.