Bernice Shepherd

As the cleanup from the flooding continues, many people have been left homeless, traumatised and wondering if and when this is likely to happen again.

It is true that this weather event was extraordinary, dumping several months’ worth of rain on south-east Queensland and northern NSW in the space of a few days.

But with climate scientists predicting more frequent and more severe weather events like the ones we have just experienced, what can we do to reduce the impact of future rain bombs?

Some believe that an engineering ‘solution’ is the only option for flood mitigation.

But is more infrastructure in one place the solution to a whole of catchment problem?

People living on the flat land near the new Pacific Highway might assess that infrastructure can create more problems than it solves. And how will an engineered flood mitigation response for Lismore impact on everyone living downstream?

A band-aid solution applied to the wound will not address the underlying problem which, other than climate change, is a damaged catchment.

According to the Wilderness Society, despite being the least populated, Australia is “one of the worst developed countries in the world for broadscale deforestation”.

Since colonisation we have cleared almost half of our forests, with the greatest rates of forest clearing since the 1970s in south-east Queensland and northern NSW.

In 2017, the State Government significantly added to the problem by relaxing existing biodiversity and conservation laws, precipitating a land clearing free-for-all.

When land is cleared, most often for agriculture, forestry or development, it loses its capacity to absorb rainfall and to reduce the amount and speed of runoff.

Research around the world has consistently demonstrated that landslides, flooding, and in one case storm activity, become significantly worse in areas where deforestation has occurred.

With land clearing in NSW rising 60% since the weakening of conservation laws, is it a coincidence that vast swathes of the coastal regions have experienced unprecedented flooding in 2022?

There is one significant, comparatively inexpensive and simple thing we can do to mitigate flooding in our region, and that is to plant more trees and stop cutting them down.

In a natural forested landscape, rainfall is impeded by leaves and branches on its way to the ground – anyone who has stood under a big tree in a deluge knows how much rain a tree catches.

The water that does reach the ground is sucked up through tree roots and stored in the tree, to be transpired later. This means that the amount of runoff from a native forest is less than runoff from bare paddocks or urban areas.

The soil also has a role to play in soaking up rain. A forest floor is full of organic matter from composted leaf litter and forest debris. This organic matter creates a soil that acts like a sponge to absorb and retain a larger amount of water than land without. (This ability of forest floor soil is also one of the reasons why land with trees is more drought tolerant than land without.)

Conversely, when rain hits bare compacted soil, there is nothing to slow it down or soak it up and the water runs off, often taking large amounts of topsoil with it. The result is a river system that fills much more quickly with water that deposits topsoil, making the river shallower over time and quicker to break its banks.

Urban environments also exacerbate flooding. More roofs, pavements, roads, driveways and patios mean that water runs straight off into stormwater drains and watercourses rather than being absorbed by the land. In contrast, a garden with trees and shrubs will act like a forest, holding onto more water than paved driveways or simple lawn (though lawn is better than a hard surface or fake lawn).

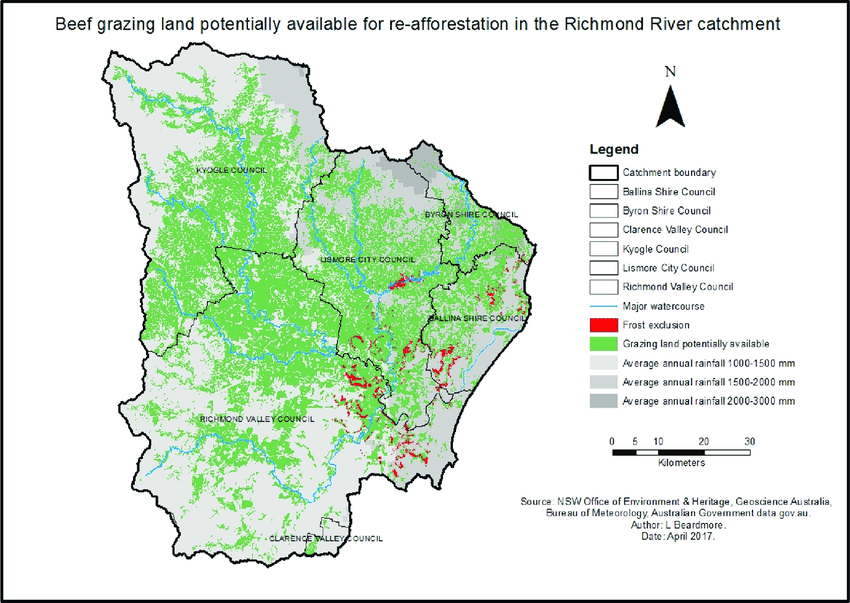

Reforestation is something we can do ourselves. We can plant trees everywhere – on farmland, in parks, on riverbanks and in our gardens. The more trees there are to soak up the rains, the better our capacity to reduce flooding. We can’t stop a rain bomb, but we can slow it throughout the catchment and perhaps reduce the impact.

Trees are nature’s lungs, air-conditioners, carbon sinks, habitat and water storage. They are also essential to our survival. If we want to avoid further one in a hundred year ‘natural’ disasters from becoming once in five year, or five week catastrophes, we need to start valuing our forests and bushland.

We need to preserve the forests we have and regenerate those we have lost.