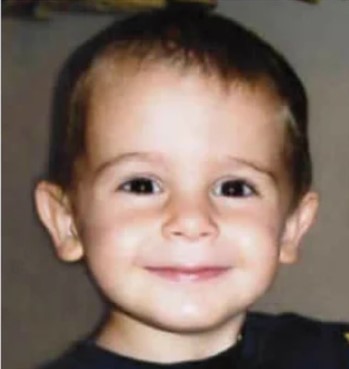

ABOVE: The death of Ryan Saunders led to important changes in patient care. Photo: Contributed

Susanna Freymark

Ryan Saunders died in hospital.

He was nearly three years old. His parents were worried he was getting worse and didn’t feel their concerns were being acted upon by medical staff.

They were right.

Ryan had a streptococcal infection that was not diagnosed and that led to toxic shock syndrome that killed Ryan.

This was in 2007.

When Ryan’s death was found to have been preventable, the Queensland Department of Health made a commitment to introduce a patient escalation process to minimise the possibility of a similar event occurring. It is called Ryan’s Rule.

Currently there are 164 hospitals using Ryan’s Rule in Queensland.

In NSW, the same system is called REACH. It stands for Recognise, Engage, Act, Call, Help is on its way.

Both are used only when there are concerns a patient’s condition is getting worse or not improving as expected while they are in hospital.

I was that patient in a Brisbane hospital, getting worse and in more pain than I’d ever known. I had acute pancreatitis caused by gallstones.

Frequently, a nurse or doctor asked about my pain level – “On a scale of 1 to 10, 10 being the worst, where is your pain?”

“Nine,” I whispered every time.

Ten was dead, but I didn’t say that. It didn’t seem funny at the time.

I was in hospital for 10 days, then at my daughter’s house in recovery for five days and now at home – still housebound but able to do minor tasks.

For a healthy (I thought), 60 year old, with lots of energy and an “I am bulletproof” attitude, getting sick in such a sudden and dramatic way was a shock.

I never thought I’d be coiled on a hospital floor in pain. Not me. That happened to other people.

“The floor is dirty,” the nurse at the first hospital said.

I wasn’t able to curl inside myself on the narrow hospital bed. A dirty floor was the least of my worries.

The nurse dropped a pillow down to me.

My ordeal began when I was on my way home driving along the Mt Lindesay Highway after visiting my mother in Brisbane for her 84th birthday.

I felt terrible and was vomiting into a plastic bag.

I knew I had to get to a hospital or I might crash.

My concern was for my two dogs in the car.

When I found the small hospital, I tied the dogs up outside in the shade, asked Reception to give them water then doubled over and pleaded for help.

It would be days before I felt I got the help that made a difference.

My blood was tested. I was moved to another hospital in Brisbane and given fluids but the pain didn’t abate. It was relentless. I stood at the edges of myself staring at that precipice of being human and wanting to get off. It was a scary place, with its haunting vulnerability — “please stop the pain” was all I could say.

The doctor said I needed surgery to take my gallbladder out. Before that, the pancreas, the centre of all this distress, had to fight the infection down.

On day three of nil-by-mouth waiting to be scanned, my daughter could see me going downhill. She had a friend who was a doctor who advised her to enact Ryan’s Rule. It was a 40-minute phone call.

I knew nothing about Ryan or the rule until a woman who said she was the hospital registrar stood by my bed.

“Your daughter has enacted Ryan’s Rule. Do you feel you’re not getting proper care? Do you….” She was abrupt, aggressive.

I couldn’t answer her questions, I didn’t know what she was talking about.

I would have done anything at that point for a sip of water. Just to wet my parched lips.

But the care ramped up after that. The doctors stopped joking about me getting a scan and it finally happened. I was given oxygen that was warm and funnelled into my lungs at great speed. I was on half-hourly observation. I was given a button I could press to administer pain relief. At regular intervals, I was given anti-nausea pills and countless other tablets.

When my daughter told me what she had done, I admired her bravery.

“That can’t have been easy,” I said.

She had a resolute look in her eyes. She was the lioness protecting me. As I had done for her as a baby. This reversal of mother and child made me feel even more vulnerable.

What about patients who don’t have someone to advocate on their behalf? Or don’t speak fluent English? Or fear authority?

Ryan’s Rule or REACH in NSW at least provide a process for making hospital care better.

The sorrow of Ryan’s parents at his tragic death had led to a process that helps others and saves lives.

My heart fills for what came after the little boy’s untimely death. It swells further with pride for my daughter standing up for me.

Everything changed on November 11. I was the vulnerable one. I needed help.

Eighteen days later, I sit on my veranda ever so grateful to be upright drinking a strong coffee out of my favourite pink mug.

The moo of a cow blends with the staccato cry of an eastern koel and the sound travels across the soft hills surrounding the village where I live.

The coffee tastes good.

I’m getting better. And I have much to think about.

I write this article because I want everyone to know about Ryan’s Rule and REACH, in case you need it to help someone you love get better.

To give you a voice when you need it most.